MAGORINO: Magnitude-only fat fraction and R2* estimation with Rician noise modelling.

This is a 2 minute summary of:

What is the problem?

MRI is a powerful method that can provide incredibly detailed information about biological tissues. However, when tissues contain multiple compartments (for example, water and fat), we cannot always tell which of the compartments the signal has come from - the MRI signal coming from the different compartments is added together and ‘mixed up’. In order to interpret the images correctly, we need to separate the information coming from these tissues. Performing this separation can allow us to precisely measure the contribution of signal from each compartment (e.g. water and fat), and also allow us to accurately measure other properties of the tissue (such as the decay rate) which also provide important biological and clinical information.

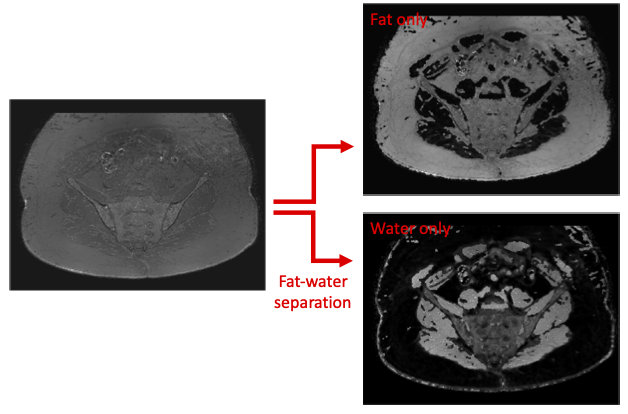

Figure 1 - Fat-water separation. In order to interpret our images correctly, we need to separate the signal from the raw images (which in this case has very little contrast) into fat signal and water signal, allowing us to generate fat-only and water-only images.

How can computational MRI help?

Computational MRI can help us to separate out the signals coming from different ‘species’, such as water and fat, on the basis of the frequency at which they resonate in the MRI scanner. We do this by first acquiring signal measurements at multiple different times in the MRI experiment. The way that the signal behaves over these acquisitions with different timings depends on the proportion of water and fat. To determine precisely how much water and how much fat is present, we use an algorithm which finds combinations of tissue parameters that make the observed signal measurements most likely:

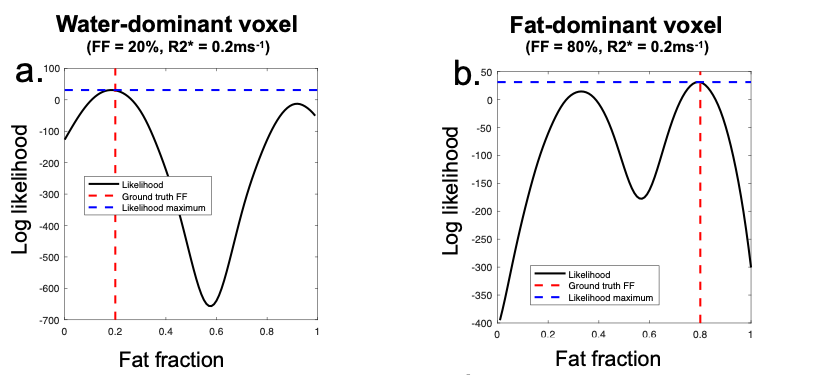

Figure 2 - Finding the most likely solution. In a water-dominant voxel (a), the true (low fat fraction) solution can be identified on the basis that it has a higher likelihood than the alternative, high fat fraction solution. In a fat-dominant voxel (b), the true (high fat fraction) solution can be identified on the basis that it has a higher likelihood than the alternative, low fat fraction solution.

Having separated the signals from the two species, we can define the fraction of the signal coming from fat as the fat fraction (FF) or, if other potential confounders have been accounted for, the proton density fat fraction (PDFF). We can also measure the decay rate, R2*, over the measurements, which provides valuable information about particular tissue constituents such as iron and calcium.

What are the limitations of existing methods?

One of the key difficulties is that the MRI signal does not only come from water and fat, but is also contaminated by noise, which is an unwanted, random error in the signal. If unaccounted for, this noise dictates that the apparent most likely solution does not always correspond to the true solution. This phenomenon causes bias and imprecision in our assessments of tissue properties, reducing the value of the measurement for scientific and clinical purposes.

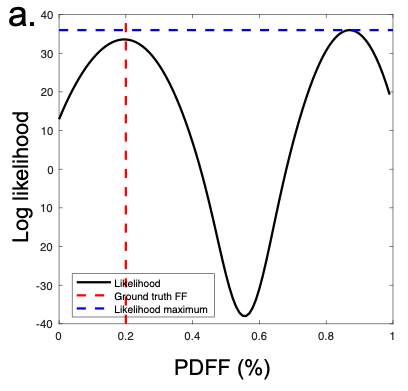

Figure 3 - Failure of existing methods in the presence of noise. In this example of a truly water dominant voxel, the true (low PDFF) solution has a lower likelihood than the incorrect, high fat fraction solution, leading to selection of the wrong optimum.

How do we propose to address this?

To address these issues, we propose an algorithm known as MAGORINO (Magnitude-Only PDFF and R2* estimation with Rician Noise modelling). With MAGORINO, we use a mathematical model of the noise in the signal, such that the more likely solution does in fact correspond to the ground truth solution in a greater proportion of cases: we achieve the situation in Figure 1 (rather than the situation in Figure 2) with greater frequency.

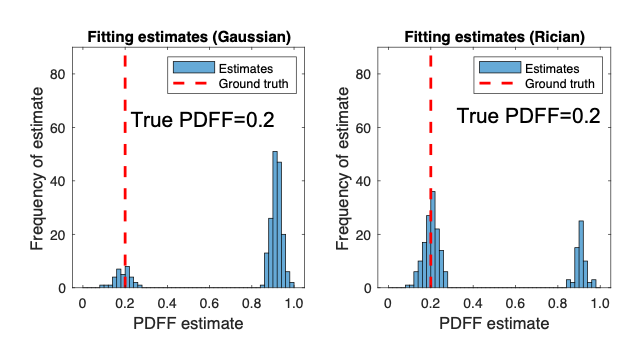

Figure 4 - Improvement in selection of correct optimum with MAGORINO. The histograms show the frequency with which different proton density fat fraction (PDFF) estimates are chosen. Ideally, the estimates should lie close to the ground truth (red line). With the conventional method (left), a large number of the estimates are incorrect (swapped). With MAGORINO (right), the large majority of the estimates lie close to the ground truth, producing a substantial reduction in bias.

How can MAGORINO help us in practice?

MAGORINO has several key advantages from a the perspective of both standard radiology practice and for the purposes of clinical trials.

Firstly, it uses data which is easily available from any scanner, without the need for specialist software or research agreements. This should make it possible to implement MAGORINO across multiple scanners, without the cost associated with specialist research packages. This could be valuable in large trials, in for use centres/countries with limited access to funding and when using older or non-clinical systems.

Secondly, the use of the noise correction model should make the measurements robust to variations in field strength and scanner settings, such as the size of the voxels in the image, making the measurements more directly comparable across scanners.

Thirdly, it does not rely on modelling of variations in the magnetic field across the image, making it more robust at the edges of the scanner, where conventional methods often fail. These problems may be particularly important for whole body imaging, when imaging near metallic artefacts and at high field.

These strengths could facilitate implementation in clinical trials and simplify widespread translation into standard NHS care.

Is the code available?

Yes - the code is available here

The specific release accompanying the paper is available here.

For discussion or further information, feel free to get in touch at t.bray@ucl.ac.uk